Lea aquí la versión en español de este artículo

What does systemic racism imply in the United States? Why has it triggered the recent massive social and political demonstrations, beyond the anti-racist movement? What is the scope of this mobilization and what does it express? Reflections of a professor and veteran of the social struggles in the USA.

I’m a white man, 73 years old. My interactions with the police have stemmed from participating in political protests and civil disobedience; being stopped for speeding, burned-out tail lights, and other driving or parking violations; being caught shoplifting by an employee at a store, who then called police; being suspected by a neighbor of causing strange noises in her attic; putting up posters on private property; and on one or two occasions having called the police myself to report vandalism or damage to property as required by insurance companies. In the political protests I have occasionally been swatted with a baton, had tear gas sprayed at crowd I was part of, or been sprayed with chemical irritants or had my arm twisted while being arrested; I’ve never been in jail for longer than one night. In the other incidents I’ve met with no use of force at all, and no arrests. I’ve never had police point or shoot a firearm at me personally. I owe this degree of safety mostly to what I stated in the first four words of this essay: I am white man. Not a black one.

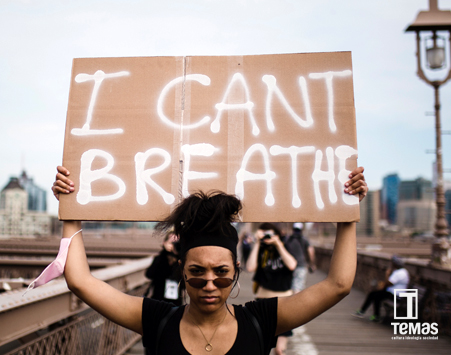

This difference is the proximate cause of the unprecedented wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations that have occurred day after day in all fifty states of the U.S. Thanks especially to videos recorded by private citizens on their cellphones, and also to videos from police dashboard-cams and body-cams that exist due to reforms won in previous waves of protests, it has become painfully obvious to a wide range of estadounidenses that African-American males (and females, but especially males) are subject to more police violence than white ones, and probably than other ethnicities too, though Latino men are also a target. Black Americans have always known this, from lived experience. If opinion polls are reliable, in the past few weeks the understanding of white Americans about the use of state violence against African-Americans has shifted dramatically; for the first time, a majority of white Americans say that they recognize the disparity and discrimination. That is part of why young European-Americans, Latinx-Americans, Asian-Americans, Muslim-Americans, and Native Americans have been present in the protests in large numbers, as any photo or video will show.

The underlying cause of the wave of protests is deeper, and is summed up in the slogan: Black Lives Matter. The creation of African chattel slavery in North America four centuries ago, which provided a significant part of the workforce for U.S. capital accumulation and prosperity, required a worldview that saw African and African-descended people as less than human, their lives and safety less important than those of others. Despite the elimination of slavery after 250 years, and the victories of the mid-20th-century Civil Rights Movement in ending legal discrimination and segregation and gaining more access to voting rights and local political power, black lives still matter less than white ones in the distribution of resources, respect, and safety. And one of the manifestations and justifications for this systemic racism is — as it has been since the time of slavery — the view of black males, even school-age boys, as inherently violent and threatening. (Cuban readers with access to Hollywood movies and

TV shows or Miami nightly news featuring crime stories need look no further than these sources to get the idea.) As Michelle Alexander argues in her book The New Jim Crow — one of a sizeable number of books on race and racism that are suddenly sold out in bookstores and on Amazon.com because of the events of the past few week —the old legal segregation that limited the opportunities of blacks, and especially black males has been replaced in part by the “criminal justice” system of suspicion, arrest, inferior legal defense in court, imprisonment, and post-prison discrimination. More recently, the political gains under one of the two important pieces of national legislation won by the Civil Rights Movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, have been seriously watered down by the Supreme Court, which has allowed state legislators and election officials to invent new ways of suppressing the votes of people of color. The current wave of protests is led by and peopled by a new generation of African-American activists who say — once again, like previous generations — that enough is enough.

Thirdly, the current wave of protests follows three years of the presidency of Donald Trump and the right-wing Republican agenda. This article isn’t the place to try to analyze that phenomenon and its complex amalgam of corporate determination to erase the economic social-democracy of the New Deal; the fossil fuel industry’s determination to deny its role in climate change; nativist and xenophobic desires to make American white again; fundamentalist religion’s determination to restore patriarchal power, heterosexism, creationism, and other dogmas; working-class anger at the decline in well-paying jobs in traditional industries; and a proto-fascist, masculinist appeal to “strength” over “weakness.” What matters, most immediately in terms of the protests, are two things:

a) Trump is the anti-Obama. Part of his appeal has been what the writer Ta-Naheesi Coates calls, in one his essays, “Fear of a Black President.” He and his party have set about erasing almost every reform, however halting or partial, undertaken by the administration of the first nonwhite President in American history — reforms in the areas of civil rights, environmental protection, corporate regulation, protection of women and GLBTQ people and immigrants, and more. That has included ending all the federal initiatives to reform local police departments after the 2014 police killings of Eric Garner in New York, Mike Brown in Missouri, and more. I have frequently asked myself, over the past three years, “Are we seeing a long-term retreat from American ideals of inclusion and social justice? Or are we seeing the last spasm of the other American ideal — that of a white, Christian, male-dominated and world-dominant power?” I think that, for many, the protests are a way of voting for inclusion and social justice, with feet on the ground and fists in the air.

b) The three years of the Trump administration have seen the President and his Republican allies run roughshod over all sorts of laws, precedents, and norms of behavior, and abandon any respect for facts or truth. This has provoked a great wave of indignation among sectors of the population, especially the younger population. A number of observers have argued, convincingly to me, that this experience has allowed whites and others to identify with the experience of the nonwhites who feel that treatment in the flesh — first, to identify with the Central American refugees imprisoned in cages and separated from their children or parents, and now to identify with African-American and Latino victims of police violence. Allowing and enculturating police officers to act (toward black people) as if they are above the law and to invent false narratives that justify their behavior is parallel to allowing the President to act in that way. And most recently, the administration has completely bungled the opportunities to control the COVID-19 pandemic — with frightening effects on health and, as a result, on economic security. Ironically, one effect is that there are many young people who are angry, who are unemployed or working from home, and who have been suffering from isolation and felt a longing for collective action.

In brief, the foregoing is my attempt at an explanation of the causes of the protests, the breadth and depth of the actions, and their participants’ determination not to give up despite repression and possible health risks from COVID-19. (I should stay that protestors and protest organizers have been very pro-active about wearing and distributing masks, and also to urge participants to try to get tested for the disease. Whether this is enough to avoid significant contagion is something we will probably learn within the next few weeks.)

Hindsight is much easier than foresight. Postulating causes is much easier that postulating effects. Let me offer three questions and some possible answers about what might happen next:

What can be fought for and won at the local and state levels?

Systemic racism is a national problem. But policing and the provision of social services are done by local governments — cities, towns, and counties — and state ones.

There have, so far, been two demands for local government response that have most consistently emerged from the demonstrations. One is to fire the police who have killed unarmed or fleeing or already-arrested persons of color, and further, to put them on trial for murder; and, in parallel fashion, to discipline officers who have used unnecessary force again demonstrators. But there is a second demand that goes further. Seeing that past efforts to reform the police through training or oversight have not succeeded in preventing police violence, the newly popular demand is to “defund the police.”

Already, the first demand has produced results. In Minneapolis, a murder charge has been filed against Derek Chauvin, who killed George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for nine minutes, and lesser charges have been filed against the other three officers present; all have been fired from the police force. In Atlanta, Garrett Rolfe has been charged with murder and other offenses in the shooting of Rayshard Brooks; the other policeman at the scene has been charged with lesser crimes but not, as of yet, fired; the police chief of Atlanta has resigned. In Buffalo, New York, in Ft Lauderdale, Florida, and elsewhere, police have been suspended without pay for assaulting demonstrators (white and black). In Dallas, Texas, the police chief has issued a new regulation of “duty to intervene” that requires other police to take action if one of their colleagues is using excessive force against a civilian. In many other localities, cases of police violence that had been ignored for weeks or months are now being investigated by authorities. Also in Buffalo, the city council has requested investigation of the the case of a black policewoman who was fired in 2008 after she intervened when a white officer was choking a black citizen who was already in handcuffs.

Still, of course, there are many other localities where no other action has yet been taken. In Louisville, Kentucky, investigation of the killing of Breonna Taylor has been taken over by the state attorney general, but there are no results or actions as of yet. (Taylor was shot in her bed by police in an exchange of gunfire with her boyfriend who thought the police who battered down front door — in pursuit of a man in fact who had already been arrested elsewhere — were criminal intruders.) “Justice for Breonna” remains a key slogan at the nationwide protests. So does “Say Their Names,” a reference to all of the other victims in the recent past; in most of those cases, little or no action was taken against the police who killed them.

Equally or more important, there has been some local government action in response to the demand to “defund the police.” The demand is a shorthand for many different possible actions, but the general idea is that the whole system of policing is corrupted by racism and an addition to the over-use of weaponry and lethal force, so public safety mechanisms need to be re-invented from the ground up. Many police actions respond to minor crimes or nuisances that are not crimes at all, and these incidents could be de-escalated or prevented by taking the millions that cities and towns now spend on police forces, and redirecting that money to employing social workers, mental health workers, and supplying other services — and to improvements in education and job opportunities. In Minneapolis, the mayor and city council have committed themselves to doing just this. In Los Angeles, the city council voted to “study” ways to cut the Police Department’s budget by 10% and divert those funds to other uses. Similar or larger cuts have been proposed by city council members in many other localities.

This will, however, be a long and uphill struggle, facing fierce resistance from police unions and “law-and-order” politicians. Due to the division of powers and budgets among levels of government, it will require votes by state and county governments, and in many cases one side or the other will resort to state or city referenda where proposals will be subject to popular votes. There will be many debates and contending characterizations of the meaning of “defund the police.” There will also be debates within the trade union movement about whether to regard the police unions as defenders of workers’ rights or as pressure groups that support state violence against working people.

What will the effect be at the national level and in national electoral politics?

Right now, contending police reform bills have been introduced in the Congress by Democratic and Republican legislators in the chambers the control (House of Representative and Senate, respectively). Neither proposal comes to ending or reducing federal funding for local police departments, but the Democratic one goes much farther than the Republican one in that it makes officers accountable in federal court for uses of unjustified force and it makes funding of local departments contingent on their taking action to eliminating racial profiling (questioning and detaining members of some races more readily than others). President Trump has consistently encouraged the use of force by the police; sought the support of police unions and white, right-wing paramilitary groups; and characterized the demonstrators as anarchists and terrorists. The fight at the congressional level will be not only between parties but also within them, as many Democratic Congresspeople will face pressure from supporters to take more radical positions, and some Republicans may break with Trump on certain specific details. The fight will continue into the next presidential administration and the next Congress. The chances of the movement being able to win any significant legislation on policing, racism, and inequality will be much greater if Trump and the Republicans lose control of the White House and the Senate in the November election.

About the effect of the protests on the presidential election, I can only say that most attempts to predict the outcome of the 2016 election were wrong, anyone who tells you they can reliably predict what will happen in 2020 is lying or deluded. In my mind, I hope the election will be seen as a referendum on the question I described above, about which “America” the millions of voters want to have. I fervently wish for, and will work for, an overwhelming repudiation of Trump. But that may not be how many voters construe the choice, and some of those who do see it that way will choose the old, bad vision.

Trump’s opposition to police reform and his denial of the existence of systemic racism are obvious. Clearly the participants in the protests and the great majority of their sympathizers will not vote for him. How many of them will vote for (and try to convince others to vote for) Joe Biden is much less certain. Biden (much like Hillary Clinton, much like the rest of the Democratic Party political establishment) has had a very mixed record over his long political career on police and crime issues and on specific remedies for overcoming racism and economic inequality. His loyal service as Barack Obama’s vice-president — no other white politician in the history of the United States, of course, has served as the deputy of an African-American president — and his perceived better chance of beating Trump earned him the support of crucial older black voters in the Democratic primaries. At the same time, he has so far been uninspiring to the younger demographic, black and otherwise, leading and participating most actively in the protest, who are much more likely to be supporters of the policies championed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, or Elizabeth Warren. And among the many unpredictable factors in this election is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on who will take the risk of showing up at the polls, and to what extent voting by mail will be available as an alternative, and to whom.

What new, multi-issue coalitions will emerge from this wave of protest and politicization?

The protests since the killing of George Floyd have involved and energized thousands of people, probably tens of thousands of people, who never participated in political action or spent much time thinking about political strategy before. The same is true of protests in recent years over climate change, over immigration, over income inequality, the 2017 Women’s March and its successors, actions for increased access to health care, and other issues. The COVID-19 epidemic has not given rise to mass protests or demands, but its disproportionate effects on non-whites and lower-paid essential workers are obvious, as are its connections to failings in the private, for-profit health care system. To what extent will these movements coalesce into multi-issue and multi-racial coalitions or forms of cooperation that can inspire participants to feel represented and respected by the leadership and the demands?

That is probably the most important question of all.

Deje un comentario