Puede leer aquí la versión en español de este artículo.

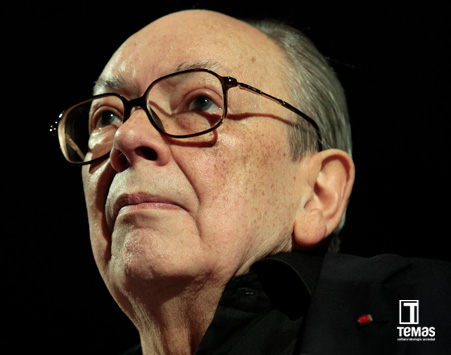

Alfredo Guevara has just turned 95. For Temas, his critical accompaniment, farsightedness, and steadfast support through thick and thin continue to be more than that of a patron saint. A rare example of an intellectual and political leader of culture, a revolutionary sense of the truth and uncompromising lucidity and a heretic thinking confronted by dogmatists and renegades alike were his identification marks. So were his way of pointing out deficiencies or stating his disagreement without putting labels or seeing himself as a supreme-court justice, his criticism of the government apparatus—at times very harsh but alien to the demagogic art of target shooting— and calling a spade a spade. In cloudy times like these, when the debate of ideas is mistaken for ideological commotion, we share again his words in the presentation of the issue that Temas devoted to Transitions thirteen years ago.

No intellectual movement, school of thought or trend in the development of science or a science, an artistic group, or a defined ideology or research in any field, can do without a means of expression. Even less so in times of revolution and expected changes—whether or not the obligation and prophecy of change are entirely fulfilled—not in an atmosphere of arbitrariness but of adjustment and improvement based on experience and its results. I cannot imagine the Revolution, not just our own but the concept itself, or the image of it that I need as a filmmaker, in terms of transition. Based on our recent and not so recent historical experience, this word is linked to pacts, concessions or slow-moving processes that, when rushed, get closer to the distortion of reality as its essence crumbles and makes room for another that prevails victoriously in the midst of such disintegration. I understand, accept, enjoy and use such a huge and productive effort of reflection, analysis, dissection and speculation whenever I get my hands on a journal like this issue No. 50 of Temas. Not just the one I am commenting on now in my own way, but also all the others that, as a feat of intellectual and political heroism, have paved the way for this issue. I am not forgetting those devoted to such important and provocative issues as Cuban-American culture, our troubled relations with the empire, the vicissitudes of the economy and its relations with ideologies, race and racism, sexuality, the world on the margins, and always Latin America and the US both in the background and in the foreground. Here we are in issue 50. The journal lives because it survives and, for that and other reasons, Rafael Hernández not only lives honoring others and himself in this way, but he turns out to be, unwittingly, a survivor. How complicated it was, for a long time, to dodge calmly and honorably, as befits a revolutionary, the hounding of Stalinist officialdom and its coercive resources, which still exist even if, fortunately, now they have to live and even reproduce like a wet sparrow!

What I most admire and respect and what unites me with Rafael Hernández is that way of being revolutionary. It is not, nor will it be the only one, or the only possible one, as the Lord's ways are infinite. However, it is the one that I most admire, built on the serenity and dignity of the revolutionary who works more and more and builds without truce, concessions, or tears.

There are no shortcuts in the field of thought; to be or not to be has an immediate answer, to be always. And besides, there are no monoliths, and when we feel and even see a presence that admits no doubt or pretends to do so, we must know that it is a mirage and that one day, sooner rather than later, every house of cards will fall under the touch of this or that little wind or gale.

Only knowledge will provide sound building foundations, and reality, its object and clarifying matter, is so complex, so mobile, and so absolutely or definitively unassailable that every conquest achieved entails new goals. We only arrive at this dream of truth by approximation. Fortunately, the absolute is only a tentative concept, a way of speaking in order to understand ourselves; every point of arrival does nothing but announce the departure. That is why journals that appear and disappear, fulfill their function for a period, and allow us to appreciate the extreme complexity of a reality that knows about neither monoliths nor absolutes, or journals that—perhaps like Temas—live on and start anew in each issue, are a haven to review our accomplishments. They are the oasis that our memory affords in print, the memory that can be (partly) the source or support of the hardest things, those which survive in our experience and go on being and enriching culture. That is the case, in their own time and circumstances and for that time and need of being, just to mention some illustrative titles, of Memorias de la Sociedad Económica, El Habanero, Patria, Revista de Avance, Orígenes, Nuestro Tiempo, Ultra, or Revista Bimestre Cubana. Also Lunes de Revolución, Cine Cubano, La Gaceta de Cuba, Pensamiento Crítico, and Revista de la Universidad de La Habana, Revista del Ministerio de Industrias, Cuba Socialista, Teoría y Práctica, Revista de Información y Traducciones, Criterios and Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, etc., etc.

Let it be quite clear that I did not intend to be thorough. So much so that I will not dwell on that other formula, force, channel, tube that is called the Internet and e-mail, a formula that allows everything, the valuable and the superfluous, the rigorous perhaps, maybe, sometimes, and the trivial that sometimes, perhaps, maybe, can also verge on indignity...

All journals, whether or not I mention them here, have served me as an example. And as evidenced by a more complete list that someone mentioned in the symposium that followed Fernando Martinez’s more than masterful lecture at the Higher Institute of Art a few weeks ago, they have turned out to be as many as the views about our life, society and future that they discuss for attentive and sometimes for deaf ears.

Could it be the same debate that this 50th issue intends to expand for both the attentive and the deaf?

Upon addressing unsolved problems, does each journal or publication—depending on its scope and audience and regardless of the issue at hand—provide in its reflections or suggestions a view of what Temas has approached as “transition-transitions”? It’s what one of the authors included in the summary calls “transitology”, coining a term that he hopes will be clarifying and I can’t say for sure if it is funny or distressing.

I will say why, not to argue but to be part of the fascinating debate that this 50th issue of Temas addresses under the generic title of "Transitions and Post-transitions".

I would love to be a great theoretician and develop such a passion for my theories and go so deep into them that I can make them happen by reliving them in my mind. Instead, I have to make do with my experience, perhaps valuable but certainly rich, varied, disconcerting and inserted in the history of the 20th century, in different latitudes and always as a minor protagonist, sometimes so, so minor that my testimony will only have the value of presence. I was very young, almost a teenager, when I came into contact with the Spanish anarchists who came to Cuba; they were, they called themselves, libertarians and they instilled that ideal into me. The fact is that the Havana generation of which I am a part vibrated with the Spanish Republic, with its communists, its socialists and its anarcho-libertarians. Those revolutionary Spanish professors who had lived through the first chapter of freedom and fascism—the struggle that preceded World War II—brought to Cuba the experience of a social revolution with its good and bad choices and that of the purging of the latter, in a clarifying reaffirmation that materialized in reflection and inter-solidarity. They all had become first of all Republicans. Many years later, when the transition arrived—to use this time the term that the Spaniards willingly turned into a model—so much time had passed that I wondered if the returns were possible. María Zambrano labelled “transexiled” the thousands of people who came to make Latin American lands fertile again; those who returned were also able to make Spain fertile again and release it from the horrors of the tambourine soul into which Francoism had plunged it. With the living and the returned came the memory and the work, along with the principles that those who stayed in our countries for good defended until the end. It was not until the last two years, after a decades-long wait, that the transition—described as model for being peaceful, useful and well calculated and perhaps the only possible one—began recognizing, in the Republic and in the singularity of such a historical experience, the ethical values and heroic courage of its protagonists. They were the purest essence of the Spain that had to be. These days I could see on international TV the newly discovered and recently restored image of some of the 300,000 Republican refugees who arrived in Mexico under the protection of General Lazaro Cardenas—that is, of the Mexican Revolution that had shaken the lands of America, and mainly those of Mexico, harder than all its ancestral earthquakes together. Our Revolution, a paradigm, a Revolution that preceded the Russian one, which I want to stress and go back to later on.

I will say the key word at last, the one that I wanted to pronounce point-blank: Revolution! That is the subject of these, my reflections, in the presentation of the 50th issue of Temas.

Revolutions are cataclysms, and as they move from one stage of organization to another, rationally uprooting a society in hope of structuring, I mean, building another, that cataclysm is compulsory and not—of this I am convinced— a simple transition from capitalism to socialism, as some of our authors have stated. I cannot help feeling astonished that such a recurrent phrase seems to be hell-bent on replacing what drives the life of an era. Revolution, like this, with a capital letter and proudly pronounced as a major word. In the case of Cuba, this new terminology is for me, to use the author who starts off from a new science or branch, transitology, a resource to describe this game or formal resource or method as what seems to be escapatology, evasionology or academiology. Revolutions are revolutions, and ours begins with a bloodbath that was, also from its birth, one of sacrifice, heroism, courage and solidarity.

That day, July 26, so close to memory, marked the end of all the theories and the legitimacy of the strategies based on phraseologies and dreams, and above all on mimesis. The armed struggle was already as irrevocable as the beginning of the Cuban insurrections that gathered two revolutions on October 10, 1868 with the tolling of bells at La Demajagua: one, that of independence, a national revolution, and that of the liberation of the black worker-slaves, a social revolution. Those intertwined ingredients were gunpowder. In 1968, Fidel declared in La Demajagua with complete firmness and lucidity that the Cuban struggle had begun there: the Cuban Revolution. The Moncada garrison and History will Absolve Me had already outlined the program of the victorious armed revolution. I will go back to one moment of this text. I am many years old. After the [attack on the] Moncada garrison I was constantly persecuted and imprisoned, and I played an active part in the underground movement in Havana. I am still paying—and I do not care—the consequences of the hatred and abuse that I suffered and, even more so, the deep pain that I hold in my soul, which does not admit oblivion, when I remember my fallen comrades. We paid dearly for this, in blood, sacrifices, frontal combats. We defeated the dictatorship and the empire, and to put it better, the empire and its figurehead-dictator. We did it as a Marti-inspired army of young, very young people, like many or some of you, led by young, very young people and by Fidel, a clear-minded chief as intelligent and wise a strategist in the armed combat as in the political one. Days after the victory he gave instructions that I will never forget: “The revolutionary laws and the first of them, the agrarian reform, must be such a destructive blow to social organization that there will be no way to rebuild it.” He used other, more graphic words, at least to me as a speech lover, but it is better if it also becomes an image. In the Program born from the Moncada, Fidel had already designed, by a small country’s standards, the basic transformations that turn men into citizens, citizens into thinking beings, and thinking beings into conscious practitioners of freedom. As one of the essays in the journal rightly points out, the agrarian reform and the nationalizations were crucial to destroy bourgeois power and U.S. imperial exploitation, that is, the presence of foreign capital and the puppet oligarchy. However, we should never forget that the literacy campaign began almost immediately, followed by educational continuity and the ninth-grade goal. Peasants from all over the country visited the city dwellers; children came down from the mountains and out of the wild and the forests to study in the city. Peasant women came by the thousands to learn how to make clothes and to access or expand “their letters” and vision of the world. City teenagers spent weeks in the countryside. Many revolutions were intertwined and complemented each other in the midst of so many changes, the Rebel Army trained to gain knowledge, which is also indispensable to handle new weapons, first of all defensive ones.

I will not continue along this path. Rather than reassessing the work done in those first years, I know that the scholars, sociologists, and economists have preferred to focus their articles and essays on an enriching critical view of the formation, status and prospects of social organization and the economy in the Latin American and international context of globalization in Cuba. In them, they go beyond our country and place it in a given context. I will not evade the issue. Che Guevara discussed it with more than one objector as early as in the 1960s. A book has just been published that is barely in circulation and that brings together Guevara’s theses from those days and the internal discussions in the Ministry of Industries. Its title is Critical Notes on Political Economy. Guevara tears to shreds the Manual of Political Economy of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and the very concept of manuals. It is a monstrosity of ideological gruel, invented to support Stalinism and everything anti-intellectual that exists in the world; that is, for the enjoyment of all those who prefer to renounce thinking and any autonomous and critical analysis for, say, dogmatic-mimetic reasons, but above all for being lazy and relishing the stupid placidity of their ignorance. Che Guevara never proposed new Bibles; I do not feel obliged to recommend this, his wonderful book, and follow his theses, some of which I find more exciting than others. Yet, above all else, it is an incitement to think about and tackle problems as part of an ever-changing reality and does not allow the fabrication of formulas that should not or cannot be discarded years later if necessary.

I had the exceptional opportunity of discovering a Chilean senator who was somewhat frustrated because he had been staying at the Deauville Hotel for several days and was unable to make contact with leaders of the Cuban Revolution. He had his own theses and I took him to meet Che Guevara, and that is how I could hear by chance, as a silent witness, so to speak, part of those first conversations. Allende sincerely and profoundly believed in the democratic electoral possibility of coming to power and preparing the ground for socialism from there. He was not naive enough to establish in hours, weeks or months a society of radical socialist inspiration, but he did believe in opening very serious and increasingly rooted paths in that direction. He proved that the traditional democrat could lead him to government and he tried to go further, aiming for power and initiating long-cherished transformations. He paid for it with his life. Many years before, in 1950, I arrived in China when Chiang Kai-shek's armies were still fighting. Shanghai had fallen a few months before, in September 1949. I was part of a delegation of university students who were touring the almost liberated China, participating in popular rallies in support of Mao Tse-tung. The war was not over, so our caravan relied on troops and large-bore machine guns. We found Mao. The popular support and enthusiasm were impressive, but they had to fight to the last minute. There were pockets of enemy armies everywhere, fully stretched, advancing and retreating.

I was at the Sorbonne in 1968 when the student rebellion began, and spent all morning under the drumfire of the tear-gas bombs that had been used for the first time in Vietnam. Walter Achúgar, a very close Tupamaro friend, was dealing with the same thing. We parted company in front of a left-wing bookstore, La Joie de Lire, on the edge of Boulevard Saint Michel, and only when I managed to get out of the hottest area did I notice that my eyes were damaged. When I returned to Cuba, the ophthalmologists found a solution and saved me, but another friend from back then, the director of the bookstore and the editorial that published Tricontinental in French, was so affected that he remained hospitalized for months. One of the bombs had exploded over him. General De Gaulle (whom I admire despite everything) flew by helicopter to Germany to ask for help from the French troops stationed there. He succeeded and managed to hold his ground with their military support. However, the French State, born of a revolution that changed the world—the only one after the all-embracing Roman Law capable of imposing, guns blazing, the full structure on the entire European society and using the Napoleonic Code to restructure the State in depth and strengthen it for modernity—had run the greatest risk. That State, however, strong as few, was then on the verge of collapsing in a few hours.

It was the second time in my life that I appreciated such a structural and military weakness in the face of an outburst of a popular and potentially revolutionary nature. I had learned in Bogotá, in 1948, together with Fidel, how weak that and any other state structure could be.

In Bogotá, in the heart of Latin America, symbolically in the Andes and while the Pan-American Conference was taking place with the presence of General Marshall, the assassination of Gaitán—the most popular and beloved liberal leader in the history of that country—unleashed a revolt. The event shook the foundations of society to such an extent that it was able in forty-five minutes to overthrow the government and overwhelm its armed forces. The police and the army either laid down their arms or did not fight. Another force, “the Chulavistas”, had to arrive to stop the uprising. It fell to them the brutal role of controlling the armed people and stopping the looting and the fires that they started. Bogotá disappeared in the flames.

Again a time warp. June 1968: I traveled to Brazil. Many young and nearly rebellious students of São Paulo were linked to Acción Libertadora and very directly to Marighella; in Rio, Chico Buarque, Gilberto Gil, Glauber Rocha, Caetano Veloso, and others were leading demonstrations against the dictatorship. It looked like the French May all over again, but the army crushed that outbreak. The military police were hot on my heels, but I say it as a joke, because the same students I had met in a Paulista trench had placed me next to the pilot of an Air France plane, without a seat or a ticket, and I was already over the Atlantic on my way to Paris. They, on the other hand, went to prison eventually, and some were killed. However, the fighting continued until the defeat of the dictatorship. Those who try to move society in any new direction, inspired by any ideology or religion, be they Marxists or even reformers, radical or otherwise, must deal with risks, responsibilities, tasks and enemies not easily reduced to technical schemes. Look at the Haitian leaders or Juan Bosch in the Dominican Republic, in times not so distant or current. The oligarchic regimes, the empire and their armies suppress, crush and, if it so happens, murder. They always threaten, besiege, surround, impoverish and restrict. This is the case of Cuba; let us always remember that.

They say jokingly, what I have lived through no one can take away from me. What I have lived, the experiences that I have hardly written anything about, spring from and take hold on a certain common sense. That is what I believe: revolutions are revolutions.

They either succeed or fail. They sail with good luck or encounter difficulties, so many of them that they fail to realize their full potential, suffer periods of stagnation and become corrupted or rectified in time and are reborn with new vigor.

We had a Moncada and we had a January 1, 1959, the newest New Year in our history. Che Guevara fell in Bolivia and Bolivia has a revolutionary in the Presidency and multiplies by two its revolutionary project with an Aymara Bolivian returning the dignity of real power to a descendant of the indigenous peoples in an act of historical justice. We had a special period—we still have it, if a little less special this time—and we hope that such specialty will be shortened if we work well and fulfill the task imposed on us by the circumstances: to defend the Revolution and its essential ethics. Also, the supreme value that legitimates it: its passion for justice and truth, contributing ideas, possible solutions or, in most cases, the referential frameworks in which those eventual measures-solutions or our way of approaching them would be feasible. This issue of Temas—whether or not we agree with this or that reflection, proposal or text—meets by far one of the goals that, I dare to assume, inspired its design. Namely, to arouse new concerns among the readers, enrich those that they surely have already, and nurture the productive anguish that comes from the kind of active commitment that prevents useful thinking from sinking into the corrupting lethargy of inaction.

I always remember from those more than juvenile days to which I have referred, the strange relations that I established with Ortega y Gasset, whom I tirelessly read, not because I found him fascinating but because he provoked in me rejection and a usually turbulent silent dialogue. Not because I totally denied his theses but because I found them to be too little, almost conformist regarding progress and modernity as they were understood then. It was a time of hope for a possibly better world, and therefore not conducive to revolutions on a global scale. I still keep those books, and I love them because they made me think and debate on what I was reading. In preparing these notes, I have appreciated not the phase of rejection, which I sometimes feel rather more than consider as I read some paragraphs, but the phase of encouragement, since in the diversity of generations, responsibilities and possibilities you can discover or better appreciate a virtual debate and the presence of an active conscience. This time over in a historical period in which I am convinced that what is possible is possible, and so is what is necessary.

One of the articles in Temas quotes a phrase by Fidel, very, very well selected for this debate. It is a reference to his speech of May 1, 2002. “What is the Revolution, I dare to wonder and do it for these times?” Then Fidel answered his own question by saying: “Revolution is having a sense of one’s historical moment, and changing everything that must be changed”.

Upon the launching of Ignacio Ramonet's book 100 Hours with Fidel, I was convinced that its pages already contained a message that, recapitulating history and experience, pointed to the future. I told myself that it only remained for Fidel to do, and I hoped that it would be possible—it is happening today—was to give the new generations, those who are here and the others, messages and designs for the future. Not that I do not believe that others like him, different but valid, can emerge; or another José Carlos Mariátegui, Martínez Villena, Julio Antonio Mella, Flores Magoon, Salvador Allende, Che Guevara, Prestes, Marighella, Albizu Campos or Juan Bosch. Some succeeded others, and there have already appeared those who try to carry someone’s history through or make their own, becoming leaders of their peoples and forging the spirit of ethics and justice around the way of being necessary and possible for each epoch, period or circumstance, sympathetically and with a “sense of one’s historical moment”. We will always see, as history will prove, predictably or unexpectedly, the emergence of the necessary thinker, leader, chiefs and organizer. Capitalist barbarism, human exploitation and injustice, no matter what disguise they take upon, will never have a moment’s peace.

Why Fidel then, why dream then, or claim from him messages and designs, or wait or wish for them, as in my case? I stress that simply because I am on this platform, not because it gives me any particular significance. It is just that I have appreciated in the texts that I read more recently, in his reflections, a common presence. They all seem to yearn, in the face of new realities and exceptional, historically exceptional opportunities, for a necessary revision and revitalization of socialism.

Some would like us to get rid of the burden that hinders everything about thinking and being from the dogmatic-routine-mimetic-impoverishing conceptions of Stalinism. Che Guevara described as biblical the conceptions that crystallized and became forever unappealable. And good God, since I have to make an assessment here, I will say that they do it without any poetry. Fidel has said, and now I repeat, that what is revolutionary “is [having] a sense of the historical moment, changing everything that must be changed”.

Latin America, this or that country, Cuba perhaps, or the Revolution here, there or somewhere some others like Fidel, Che Guevara, Martí and Bolívar, but Fidel is here and now. There is no one anywhere these days, no other thinker and leader, with such authority over the new generations and a greater voice for history. No one as good as a communicator and, I insist, with as much moral authority as Fidel, who could contribute better and more productively to our reorganization and our attachment to our roots with an up-to-date and true-to-life vision. His voice can give to leftism and more specifically to socialism what they have not received yet.

Does he still have something to give? He is already in training as in the days of the University Stadium and the Federation of University Students. I discern a number of those traits in some of his recent reflections. And not a few of the works collected in Temas are pointed in some of these directions, proving that we have many a goal to rethink as we look to the future. These are not new concerns: can socialism or an approach to one or more socialist programs be reconsidered without placing in the foreground the green, the ecology, and the moral responsibility that savage capitalism and its empires have kicked down and the empire of our days is bent on destroying? Here is a flag that resizes its presence. The salvation of the planet, of human life, of every single being, cannot be absent from a socialism of the 21st century.

This socialist Renaissance, which is full of humanism, humanism above all else, primarily humanist and should and will have to be reborn, is already supported, and it will remain supported by forgotten or neglected concepts that Mariátegui had placed in the forefront. Mariátegui, Zapata and the whole Mexican Revolution did so, and more recently the Bolivian revolutionary movements that an undervalued filmmaker, Jorge Sanjinés, collected in images as important, yes, as important as those of October. That is why we will have to think, rethink and evaluate, find inspiration in the popular grassroots movements, the Landless, the women, the marginalized, and the indigenous peoples, in those who demand respect for their dignity in the framework of natural options. Even in the criminals who must be re-educated, since they are persons, for the sake of their social reintegration and self-respect, and we will have to meditate upon those other forms and demands of the peasants, wherever they may be. The revolutionaries, their university vanguard and their “academics” are usually city dwellers or become so; agrarianism, nature, ecology and their interrelationship will not be empty words. They return to their rightful place.

I have not referred to the proletariat, to the working class, and I will not do so. Its role as the mainstay and driving force of socialism calls for very complex reflection and I will not be able to state my views in a single paragraph. It would be better to propose Temas to elicit a debate, but not a Cuban, Latin American debate, on such concerns and possible answers in the midst of a second scientific-technological revolution, of a globalization that enriches and impoverishes people to atrocious extremes, and of the shaping of a new profile for society, that of knowledge.

The topic of the market, which also worries those who publish their essays in Temas, appears somehow in Fidel's reflections, and it was always present in Che Guevara’s. Right now, I would like to disclose part of one of Emir Sader’s quotations used by one of the essayists of Temas. He points out: “The struggle against a mercantilist world is the true struggle against neoliberalism, through the construction of a democratic society in all its dimensions, which necessarily requires a society consciously governed by men and women and not by the market.” It appears in Gilberto Valdés Gutiérrez's essay El socialismo del siglo XXI. Desafíos de la sociedad más allá del capital [Socialism of the 21st century: challenges to society beyond capital] and particularly in its second part, América Latina: posneoliberalismo y socialismo [Latin America: post-neoliberalism and socialism]. I am not dwelling on this essay for lack of interest in the others; it is just that I am preparing for the XXIX International Festival of New Latin American Cinema, scheduled for December, a Seminar about “Reality and/or Utopia: America Today”. That is to say, I think about the context in which the New Cinema will continue to be new or not, because that cinema emerged alongside and very often playing a role, from its level, in the fight for national liberation. We know that it is no longer the same cinema, but what will it accompany? What will be its role in reviewing, discovering and enriching not only reality, but also its ethical-poetic imagery? Osvaldo Martínez claims to be hopeful that “socialism has a second chance to rethink itself. For the Cubans, rethinking socialism involves a great deal of responsibility. It is about valuing the meaning of the fundamental things we have achieved in order to move, from them, toward that socialism of the 21st century”. End of my citation. I would like to emphasize that one of the fundamental objectives we have achieved, which we must develop and protect, is knowledge, the greatest treasure of consciousness for the exercise of freedom and responsibility, and for development.

Using knowledge and the analysis of the real reality, we could perhaps avoid the anti-market phobia that those men and women of socialism referred to by Sader, and the instrumental institutions at their service, will have to control, like everything else. Not blind forces that in the end are neither blind nor manage to mask the brutality of their goals.

Osvaldo Martínez defines such an approach to the market, which ultimately defines everything in the organization and treatment of the economic structure, as “socialism’s unresolved matter” and “extremely ambivalent phenomenon”. Still, he does not fail to bring to our attention the danger of moving to that extreme “danger which, if repressed to the point of suffocation, might have negative effects and discourage production”. I will use one of his paragraphs because it summarizes in an almost cinematographic image this object of debate and life. The market is “a spirited horse that threatens to throw its rider out of his saddle and of throwing its rider and split his head open, but at the same time, there is no other mount available, so it would have to be handled on a day-to-day basis by a trial-and-error process”. This trial-and-error method makes me think about Che Guevara; about that ‘no’ to inaction or immobility in the face of urgencies that entails availability for rectification and adjustment, a component of the anti-dogmatic spirit that goes beyond the problem of and approach to the market, but starting from the same principle.

The revolution is not just a rational process, nor can it stop being one: every blind force must be humanized.

Finally, I must finally draw your attention to two aspects about the interview with Ignacio Ramonet (included in this issue). One is the quality of the questions; the other is the importance of all the answers. I will elaborate on one that I find painfully impressive because it certainly corroborates a reality that, even if partial, is heartbreaking. Ramonet says that the new generations interested in social change who, like “the generation of the 1960s”, could see us as Mecca—I am quoting—consider us “an old-fashioned socialist country, a sort of split between Cuba and Latin America”. “That cut is a mistake,” he says. He underlines then and presents as one of the inspirations and purposes of his book, that, “what happens today in Latin America would not be conceivable without understanding Cuba”. It was about time that someone like Ramonet said so. That interview should have the widest dissemination. If the questionnaire is clever, the answers will be proof of lucidity and depth and moral courage and balance, and therefore, of rigor.

I will finish here by congratulating Rafael Hernández and his collaborators for the 50th issue of Temas and its previous ones; for standing as example of dignity and revolutionary intellectual courage; for their present and future contribution to the Revolution, because thinking is a revolutionary act.

Translation: Jesús Bran

Deje un comentario