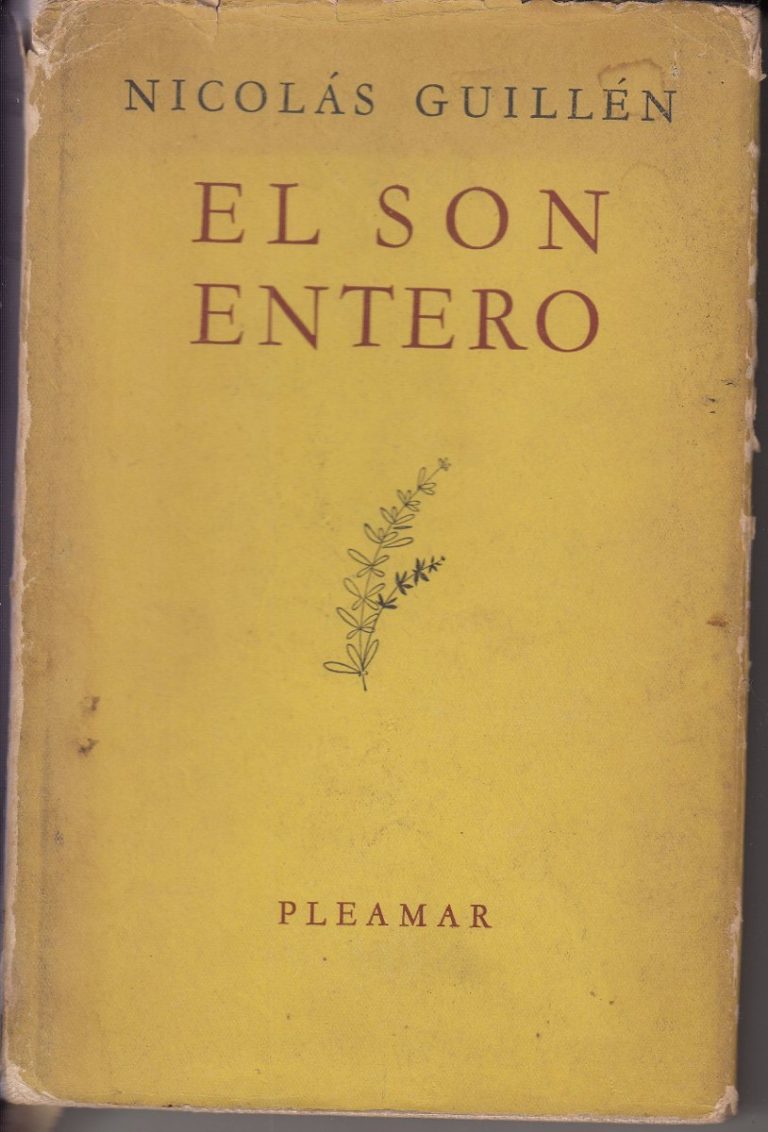

In March 1948 —it will be three quarters of a century—, which was published in San José in the emblematic magazine Repertorio Americano, [1] and under the title «Presencia de Cuba : Nicolás Guillén , poeta entero», a text due to another great of Cuban poetry Eugenio Florit , and whose appearance in this essential Costa Rican and Latin American forum was consistent with the vocation of its promoters, "to find the proper terms for a history of the culture of contemporary America", as recognized in his profile publisher . This study of Florit appeared almost simultaneously in the Colombian Revista de América , in February 1948, and it stops at the collection of poemsEl son entero, [2] a highly significant book by Guillén in the Latin American and Caribbean sphere, published in Buenos Aires a few months earlier, and seventy-five years old.

In a letter dated July 27, 1948 in Middlebury, Vermont, since he was then teaching at Barnard College and Columbia, Florit comments to his compatriot:

My dearest Nicolás: not because I was waiting for your letter — my mother wrote me that you had asked her for my address — has it not made me happy; she longed to hear from you directly, even though she had followed you through that long three-year journey you've given yourself. [3] Of course I know your book. Like that whole Son made me write an article that I called « Nicolás Guillén , whole poet». […] I did in it what I wanted to do for a long time: put you through the roof. I don't know if I will have succeeded. But I think if you read it you won't be too ashamed to be my friend. How great you are (That is, without coba, too).

And he says goodbye: «That I have been very happy to hear from you; that you do not forget me; and that loves and requires you, and admires and “requeteadmiras” your invariable, Eugenio Florit».

The synthesis of Guillen's work, his poetry, his prose (chronicles, articles, essays), his epistolary and his own life, harmoniously interrelate as the parts of a whole, of his Cuban, Antillean and universal vocation, from which his Latin American essence as a summary and finished expression of a vital, ideological and literary trajectory. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of scholars, even those who have had more controversial or partially misguided views of his work, agree that El son entero, published in Buenos Aires in 1947, is the book "that best rounds up Guillén" . [4] Unquestionably, in this, the poet advances from the territory of the language, miscegenation and ideological confrontation, to the fullness of Latin American expression.

Anderson Imbert 's idea is repeated in Cintio Vitier : "until it congeals in the round and serious fruits of El son entero ". [5] He speaks of spiritual maturity and expression of "the universal human son, with that poetry, that interruption to insist more endearingly, of American and, in the distance, Spanish lineage." And African, we would add. In a letter to Ángel Augier dated Santiago de Chile on December 8, 1946, Nicolás writes: «I have put all my books in a single volume, at the request of Losada, to publish them in that publishing house as complete works». [6]

Max Henríquez Ureña , in his still essential Historical Panorama of Cuban Literature [7] recognizes among the keys to the triumph of this book, that for the most part there is «political intention, but in it he has put to the test [...] his mastery in making committed poetry at the service of an idea “without distorting aesthetic values.”» Max gets to the core of it, pointing out that some texts cannot be classified as social poetry and citing the classic “I was walking down a path…” as a “mysterious evocation of death”. [8]Other critics recognize the importance of what is in turn the most Latin American of his books, both for its themes and for its prominence in the continental literary context. With the background of his previous collections of poems and the relationship with contemporary writers and artists of the hemisphere, the long tour of 1940 through the Caribbean and South America is the breeding ground for his poetic anointing: « Sing, Juan Bimba, / I accompany you! !” This evocation of the popular character from the plains, which A ndrés Eloy Blanco perpetuated in Venezuelan letters, is equivalent to the Cuban Juan Criollo or Liborio.

The presence of Our America in Guillén 's poetry is a topic that has already been addressed by several authors, such as Mirta Aguirre , [9] Juan Marinello , [10] Luis Álvarez , [11] among others. Presence that is also recorded in his abundant and suggestive Prose de haste, [12] and that together with his extensive and intense epistolary, which forms the "other" discourse of Guillen's work, integrates the faces of a triangle in whose center as force centrifugal we have the life of the poet. On the other hand, this diverse epistolary is the least studied of his bibliography. [13]

A minimal approach, a simple association of friends, countries, letters, chronicles and verses in the context of a long trip and a book, summarize very succinctly what could be the fundamental chapter, which from the Cuban and West Indian would proclaim the Latin American expression. But nobody better than him to attest to that accumulation of experiences. A year after the publication of El son entero, at a lunch offered at the Pen Club in Havana, in March 1948, coinciding with the publication mentioned in Repertorio… of Florit's article, and on his return from the tour of our America declares its belonging:

Ours is closer to the Latin spirit that came to us through Spain, France and Portugal, that is close to my heart, pressing it against my heart. And this walk through South America from which I now come means for any of us an unforgettable adventure, a juicy experience that teaches us how similar and even equal are the great problems whose solution we are committed to. Our cane is called oil in Venezuela, coffee in Brazil, meat in Argentina, bananas in Colombia, saltpeter in Chile, and they engender the same people's pain, the same anguish, the same misery. Fortunately, they also provoke rebellious couples. [14]

What is recognized in the discourse of the Camagüeyan, in this renewed evolution when addressing «rebellious couples», is how all the writings prior to El son entero pay tribute to fix what years ago it was in his poetic art —and where the mutations are replicated ―, beyond the fragmentary or associative, as an original discovery of creative order, an exercise that made his writing transcend. Recognizing the difference, "the other" from the margins and silences, is a sign that marks his work. In the words of academics such as González Echevarría, «the most encompassing issue of Latin American singularity and originality» constitutes that difference that «in Guillén is his Africanness» [15] .

Throughout his life, Nicolás forged a double condition: he was the greatest exponent of mestizo writing, capable of uniting the aesthetic trends in vogue in avant-garde Europe with his Caribbean, island and profoundly Cuban vision, and at the same time a indefatigable investigator of the musicality, the forms, the sounds of the language. His determination to syncretize the findings of the European avant-garde and African or Caribbean symbolism, in its fullest sense, within the trends of modernity, and incorporate resources previously considered, in a reductionist manner, peripheral, make Guilléntoday occupies a singular space in the art and history of the 20th century. His example is the result of the multiple circulations of forms and ideas supported by the avant-garde, international and transnational cultural exchanges and movements that conditioned modernism in the broad sense, long before globalization was considered in the last decades of the last century. .

«The children of Spanish and Indian were called mestizos, to say that we are mixed from both nations; it was imposed by the first Spaniards and because of its significance I call it full mouth and I am honored with it”, wrote the first advance of our literary canon, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega . One of the aspects to develop of the common origins, are the communicating vessels that make: «Despite the differences and the telluric contrasts, since the days of the colony the reaction of the Hispanic American before the world has an identity and a kinship Much larger than expected." [16]

In the case of the author in question, the predominant language is the other Spanish, "the lost language", as Ezequiel Martínez Estrada named it . In his controversial and passionate essay "The Afro-Cuban poetry of Nicolás Guillén " (a definition with which Nicolás himself would disagree), Martínez Estrada points out that one of the most important contributions of the poet to the lyric of the continent is the singularity that comes to us «by underground currents» in the use of the language: « Guilén brings the archaic culture of the preliterate peoples and the modulations of feelings that do not necessarily need the word [...]». [17]

When speaking of "the language of the vanquished", he is acknowledging an instrumental use of not only philological or poetic connotations, but above all social and historical, as a rebellious belonging to the "small human race" of Bolivarian ideology. The insurgent poet is nourished by those roots that intersect between Spain, the original cultures and Africa, but at the same time he becomes independent by taking from each one what is essential to him: «he is not dialectal, but he does not give himself, in the noblest and great of its message, to the subjugation of the language of the victors. It belongs to the defeated people. [18]

Miscegenation is the cornerstone of that transculturation that has also been called, in a more political interpretation, Latin American and Caribbean integration, but which in the subterranean history of peoples has as much force as religious syncretism, which comes from tribal magic. , going through the Santería of the barracón and the Maroons, to the official Christianity of the ruling classes, in its Catholic or Protestant variants. Recipient of the main migratory currents of the continent, whether European, Asian and African, these literatures are carriers of the eclecticism typical of their mestizo formation. One of the fundamental keys in the writings of Nicolás Guillénit is the search for that identity, finding oneself and recognizing oneself, beyond history, philosophy or religion. As his great friend, another author of national and popular expression such as the Venezuelan Andrés Eloy Blanco, would summarize at the time: «There are, well marked, the limits of his poetic empire. From them rises, like the perfume of the deep forests of America, the dark voice of the last.

Deje un comentario