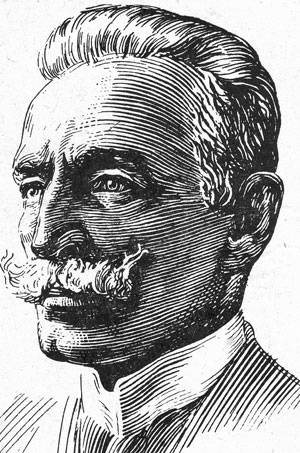

About the Author

On the anniversary of the death of the Cuban lawyer, soldier and journalist Manuel Sanguily (March 26, 1848 – January 23, 1925), we share this letter that he sent to Juan Sincero, the pseudonym of Manuel de la Cruz , and that was published in the number 31 of La Habana Elegante , corresponding to August 4, 1889 and included by the essayist and researcher Cira Romero in her book Traversing the thresholds , in which the relevance of the letter is referred to as follows:

I verified one of the most relevant moments in the development of criticism in Cuba, and the way in which our writers faced it, in what I call a triptych of ideas and concepts about what should be the expression of literary judgment. I am referring to two letters published in 1889: "To Juan Sincero", the pseudonym of Manuel de la Cruz, written by Aurelio Mitjans , "To Aurelio Mitjans", due to Juan Sincero, and from Manuel Sanguily to the latter, exposed in "La Literary criticism". Appearing in successive issues of La Habana Elegante , it is verified how they understood the way to exercise it, and the importance that the Frenchman Hipólito Taine had for our turn-of-the-century intelligentsia is evident.(1828-1893), whose positivist thought, tending to found a scientific and experimental psychology on physiological bases, had a great resonance and in literature established the theoretical foundation of naturalism.

Fragments of his work

"Literary Criticism"

To John Sincere.

Very distinguished friend:

Because you wrote to me urging me to intervene in the matter put into question by yourself and by Aurelio Mitjans about a month ago in two very pleasant letters that appeared in this weekly, and only because I don't know how not to please you, no matter how the commitment is arduous and my forces are very weak, I decide to put my room to swords, as they say in the language of gamblers; although I will have to do it with the brevity that the limited space that I have available imposes. It goes without saying that I still cannot explain to myself the desire that you have shown to know my private opinion, unauthorized and insignificant in itself. And don't want to fancy it now that I boast of false modesty. If the criticism that currently prevails is exclusively scientific, Or if alongside a scientific critique there should be another literary one in its essence, isn't that the issue or thesis that you and Mitjans were examining? Well, I believe that the criticism of works of literary art falls squarely in the realm of Aesthetics, and nothing less precise or more obscure than this science, if indeed there is a science called Aesthetics, when perhaps the studies that we call by their name are only narrow dependencies, immediate derivations, or forced corollaries of what is known by the designation of Philosophy; or as if we were to say that each philosophy corresponds to an Aesthetic that comes naturally from it; for which reason we hear at every step mention a Platonic aesthetic, another Kantian, that of Hegel, that of Schiller, that of Schelling, that of Cousin, that of Herbert Spencer… He is currently publishing volume by volume Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo the History of aesthetic ideas in Spain. Not long ago, Emilio Grucker published His History of Literary and Aesthetic Doctrines in Germany. Twenty years earlier he had printed Alfredo Michiels's History of literary ideas in France. The famous and ill-fated M. Guyau titled The Problems of Contemporary Aesthetics, a book in opposition to the ideas of Spencer and Alien, like all of his, truly admirable and, in some places, in correspondence with the work of M. Gabriel Séailles, Essay on genius in art. Twenty years before, Alfredo Michiels had printed his History of literary ideas in France. The famous and ill-fated M. Guyau titled The Problems of Contemporary Aesthetics, a book in opposition to the ideas of Spencer and Alien, like all of his, truly admirable and, in some places, in correspondence with the work of M. Gabriel Séailles, Essay on genius in art. Twenty years before, Alfredo Michiels had printed his History of literary ideas in France. The famous and ill-fated M. Guyau titled The Problems of Contemporary Aesthetics, a book in opposition to the ideas of Spencer and Alien, like all of his, truly admirable and, in some places, in correspondence with the work of M. Gabriel Séailles, Essay on genius in art.

If the very foundation of literary judgments is variable and shifting; If, in addition to his character, he is always so abstruse that he provokes radical discrepancies and constant controversies, can there be any doubt about the sincerity of my fears, the legitimacy of my doubts, and that in matters so difficult, so complicated, and so hidden, I am only sure of my insufficiency? But since you want it that way, I will compendiously expose my humble opinion, giving it for what it's worth.

In my opinion, all criticism is scientific, or it is not criticism, and all criticism, like any human work, is eminently personal or subjective. If there is a criticism that is called "literary" it is not, of course, because it lacks a scientific basis, principles that support it; but to determine directly and immediately his special point of view. What does tend to happen, and has been common and even characteristic, is that the critic knows the literary rules; but not so the laws of human nature in which they have their roots, and that by force has to be and has had to be a narrow-minded critic, superficial and without philosophy. What does a literary critic do when he examines some literary work; a sonnet, for example? He naturally considers it only as a manifestation, a form of the art of the word and especially of poetic art; and it will have to seek the conformity or deviation of the work with respect to precepts, or rules, consecrated in each era for a thousand causes, a multitude of antecedents and concomitances, and for deep, positively scientific reasons; although all of them are not known nor have the known ones been classified nor could they be organized in a complete synthesis; Therefore, perhaps, they are modified, modifying the fundamental or philosophical explanation, according to the times and the efforts and value of the investigations, always naturally in close relationship and correspondence with the intellectual and social state of each people and each moment of their existence. full evolution. A sonnet is a composition, an artificial form that expresses a mental state. So it has a psychological aspect and a technical aspect; but welded together in a very profound hypothesis, to the point that they can only be separated by analysis. It is, for the same reason, a total, synthetic, individual case, for whose examination several essences have to be concretized: psychology, physiology, acoustics, grammar, and several prescriptive ones: the art of versification, the musical art, the literary art. The critic, in addition to this knowledge, as they say in Spain, needs something higher and proper; his spirit must be elevated, he must have taste, good taste, as they call it; that is to say, that as many personal elements as there are in the same artistic works enter into his judgment. Generally such elements are predominant, for the same reason that literature is so complex and so insecure. The human feeling that originates art and the one that informs artistic works are real and efficient, although in truth very obscure, almost indefinable, and dependent on innumerable current and previous, mediate and immediate causes. Consequently, lacking a measure, "the gold meter", the door to critical individualism remains wide open.

The true work of art, well thought out as well as felt, is a synthesis. Criticism is above all an analysis. The one produces certain effects. The other seeks to investigate the reason for those effects. The true artist is a wise man who ignores himself. The critic is an artist who pretends to understand another. A musician, for example, a Liszt, has certain faculties and using them on his instrument, the piano, produces at a given moment a specific effect, which he sought and came to achieve, in the ear, in the soul of a hundred, in a thousand listeners. He had instruction from him, something like a deep unconscious thing, complicated, but real. The critic intends to unravel, fragment after fragment, one day and the next, the elements in agreement in that magnificent result; and the psychologist, the acoustician, the physiologist work for him. With those crusts he feeds and lives. If science were not incomplete, we would never see youth in collusion with daring ignorance climb the throne and decree ignominy or immortality left and right. From these slight considerations I understand what M. Taine has done and is doing. He studied moral and political sciences, I think at the Normal School. He was not satisfied, and later entered the School of Medicine. He studied there for three years, with assiduity and enthusiasm, mainly nervous physiology and with a specialization in the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. we would never see youth in collusion with bold ignorance climb the throne and decree ignominy or immortality left and right. From these slight considerations I understand what M. Taine has done and is doing. He studied moral and political sciences, I think at the Normal School. He was not satisfied, and later entered the School of Medicine. He studied there for three years, with assiduity and enthusiasm, mainly nervous physiology and with a specialization in the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. we would never see youth in collusion with bold ignorance climb the throne and decree ignominy or immortality left and right. From these slight considerations I understand what M. Taine has done and is doing. He studied moral and political sciences, I think at the Normal School. He was not satisfied, and later entered the School of Medicine. He studied there for three years, with assiduity and enthusiasm, mainly nervous physiology and with a specialization in the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. From these slight considerations I understand what M. Taine has done and is doing. He studied moral and political sciences, I think at the Normal School. He was not satisfied, and later entered the School of Medicine. He studied there for three years, with assiduity and enthusiasm, mainly nervous physiology and with a specialization in the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. From these slight considerations I understand what M. Taine has done and is doing. He studied moral and political sciences, I think at the Normal School. He was not satisfied, and later entered the School of Medicine. He studied there for three years, with assiduity and enthusiasm, mainly nervous physiology and with a specialization in the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. mainly nervous physiology and with specialty the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France. mainly nervous physiology and with specialty the brain in all its aspects. He fluctuated at that time undecided his spirit in Philosophy. Still more or less a Hegelian, he wrote a book that was a formidable kick to the "classical philosophers" of France.

Once his thought had matured, his ideas fixed in a harmonious organism, he published another book, the one he titled On Intelligence. He had his overview of the world, his explanation of the universe, his philosophy, and with it in his hand as a huge light source he could get to work. He had a method, which, according to what he said in a preface from 1866, "is a way of working and indicates a work to be done", he wanted, in short, "to work in a sense and in a certain way, and not something else". He added that in this respect the only thing that mattered was to inquire "if that way was good or not", for which everything was reduced "to practice it". He rejected the assumption that he had "what they wanted to call his system" and affirmed that he did not claim to have any either; but, to the next page, he stated that his method was derived from "the observation" that in "moral things" as "in physical things" there are dependencies and conditions (Essays of criticism and history, 1874). And the same thing has been done and is done by all philosophers: consider from superior points of view everything that seems inferior and dependent.

In this sense, who, even being complete and extremely arid preceptive, does not have his philosophy more or less complete, more or less blurred and confused? Understanding is the critic's mission regarding a work of art, as well as feeling it, as happens to almost everyone; perhaps more than most of those who contemplate it; because he feels more as he understands himself better; and to create it is the mission of the artist. To understand is to refer something to its causes and its effects, it is to place it in its table of conditions and dependencies.

Knowing, in chemistry, a body is neither more nor less than this. Only in the letters by extension of what happens with the acts of real life, are literary works qualified as good, average or bad. In a science, it is enough to point out the notes, the characters of a substance, to classify it immediately, so that it can be explained and understood. In literature, more is said and less is said, with the terms good, bad, average, which are lousy determinatives; I meant that they are very elastic, very vague and very relative.

When the properties of oxygen are exposed and numbered and agreed upon, I fully know oxygen and no longer confuse it with any other body. When they tell me that an ode is superb, that it is well done, or that it is weak, ill-adjusted, lacking in images or in excess of them, and a multitude of other connotations taken from common language and from a purely moral or exclusively literary order, I stay , as seems likely, without knowing the ode. Odes, harangues, dramas, poems, the book, the serial, the newsletter are individuals of different species, who are born, live, influence, vary, modify or disappear; they are organisms, as are words, ideas, man, society, history. History cannot be understood without psychic forces, without physical forces, without moral forces. History is a product. And the same society the man, the ideas the word and the book. An ode, an epigram, a book on any subject, are facts that have their own conditions and their natural dependencies.

They would be incomprehensible without the knowledge of the author, of his spirit; the spirit of the author cannot be explained without the knowledge of his family and race, without his biography, heredity, his personal constitution; but the author who came into the world with certain intellectual and physiological predispositions, receives constant and varied influences from the cradle, from home, from friends, from the opinions and characters of that and these, from the public situation, directly or through intermediaries. , and then from school, from his teachers and classmates, from the books, from the doctrines and beliefs that run in them or that surround him everywhere, leaving bits and pieces, lost filaments that fall into his spirit and gradually have their baroque centon; so that each individual is mentally composed of the same elements suspended in the common environment, that agree and conform diversely, like the infinite and different corpuscles and fragments in each turn of the kaleidoscope. Whatever an author, book, company, painting, symphony does, will therefore be the product of multiple factors.

The work produced, in turn, presents multiple aspects: it completely reflects a man, the author himself, his spirit, his character, his hobbies, his feelings, his ideas, and -his intermediary- society, the public, the artistic school , the dominant taste, the main tendencies; it is, in a word, total and synthetic expression.

Considered by one of its aspects it is an artifice; and in relation to its aborted or accomplished purpose, it will be perfect or deficient, complete or defective. This is its technical aspect; those are its characteristic or individual aspects.

But a book not only implies its entity as a product, and its author as a producer. The cycle of its destiny is completed with the reader, with the consumer. The set of readers, foreigners or locals, is made up of multiple beings, complex like the author and different from him, more or less deeply: they will be a few educated, ignorant most of the time, superficial for the most part, what the world is like; others will be literate, sometimes wise, sometimes exclusive, sometimes cold and selfish; already a sensitive aesthetic and vast observation; already a poor practical rhetorician and attached to his ruler and his compass; either a delicate man, or a scholar who follows some school, or who knows them all without following any; that one a disciple of Schopenhauer, the other of Spencer or Hegel; who disdainful and arrogant; who without initiative and confidence in his own judgment. Because reality is like that, everyone judges, that is, they feel and understand differently, under the inescapable action of certain, very peculiar circumstances. After all, all criticism is an impression. A man—whether he be a critic or an artist—is a temperament that acts always and with respect to everything under special conditions.

It is possible to separate in a work, and this is what frequently happens, what is seen in it as aesthetic, from everything else that is considered to be not, when everything that it encloses, or is contained in it, is concretely. This criticism is, in my opinion, incomplete and is, moreover, exposed to being arbitrary. To separate is to abstract, to produce entities of reason, to mutilate reality by adulterating it in passing.

To judge by such an exclusive procedure is to lose sight of the entire work in its intimate and particular unity, substituting for what it is or means mere abstractions that depend on the peculiar organization of a brain, that is, making a personal, accidental and variable work. The synthesis is in the product, in the artistic work, it is the work itself. Analysis seeks what is in it. Sometimes many things are found through it, sometimes no more than what the analyst thinks he sees or finds; and with these remains of a living entity, when trying to reconstruct it in a new synthesis, this mental operation will not always agree with the animated real synthesis of the author, but sometimes in exchange for an organic and throbbing body, perhaps only a corpse is obtained, an abortion or a monster. I shyly confess: criticism inspires me with respect and very little faith. Why was Shakespeare a barbarian for Voltaire, and for Paul de Saint-Victor he occupies "among the kings of intelligence" the remote place among the Olympians that Pan had, more adored by antiquity than Jupiter? A?! it is because the critic sees what he can and always sees through his own conditions and circumstances: the artistic work is, therefore, for the human spirit something very similar to Hamlet's cloud.

Yours most affectionate friend.

Manuel Sanguily,

Cerro. Havana, July 30, 1889.

Deje un comentario