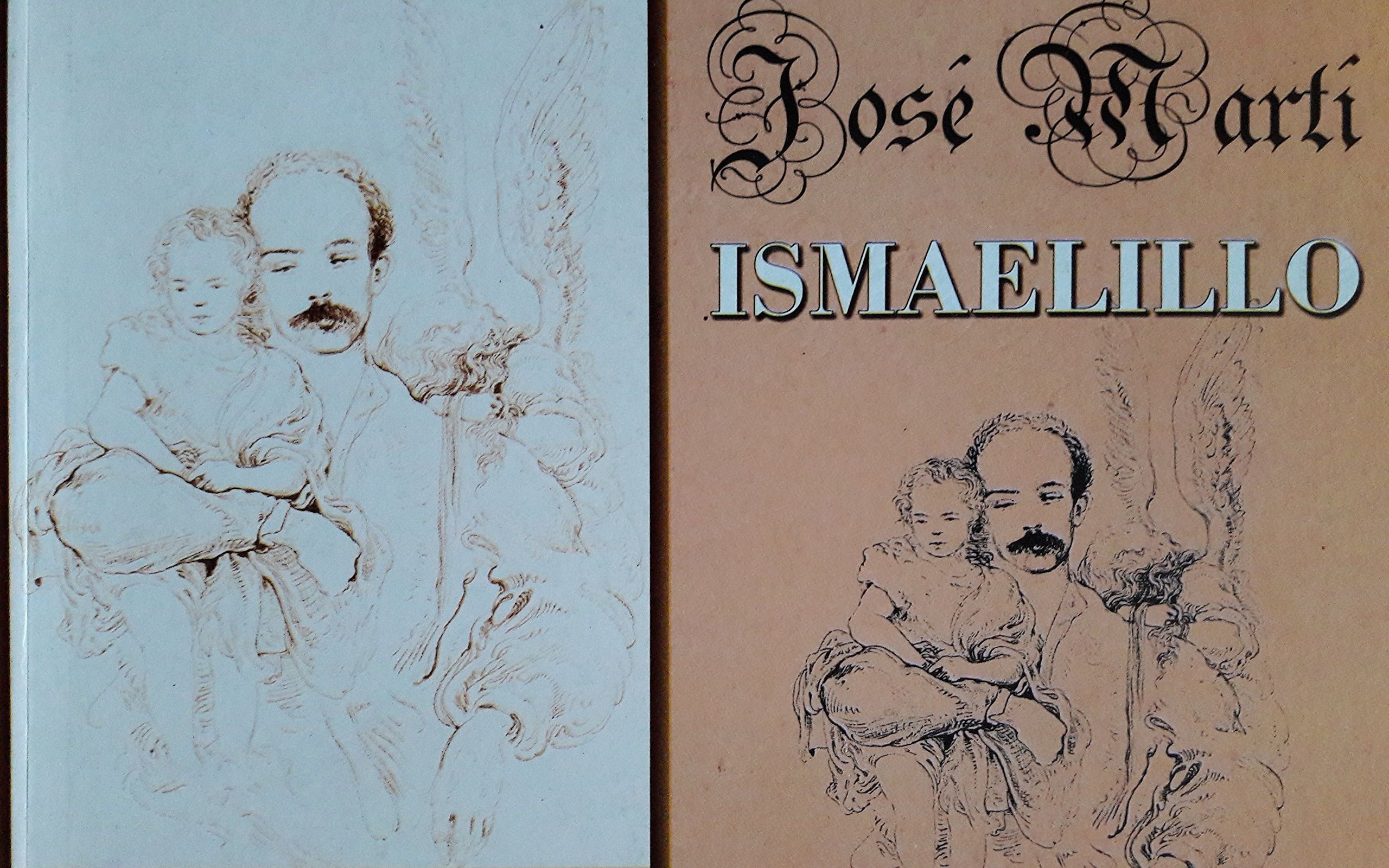

The small poem book Ismaelillo, by Cuban José Martí, inaugurated the modern poetry with only fifteen poems and a special dedication. The bard s intention was to attest to the deep love he felt for his son, and it turned out to be one of the most beautiful texts of paternal poetry written in the Spanish language.

It was written on January 8, 1881 -exactly 140 years ago-, during his trip to Caracas, Venezuela. The Apostle wrote with a fiery stroke of hurt love the deepest feelings for the remoteness of his beloved little boy.

The fervent Martí’s follower Cintio Vitier, Cuban National Literature Prize and Juan Rulfo Prize, considered that "Martí in Ismaelillo proposes a renewal of entirely Hispanic lineage, with the vitality, speed and taste for the idiomatic game at the service of deep human emotions (...) The consciousness of being creating a new American expression, that to the alarm of the stragglers it opposes that 'delight of albas', impetuous, avid and changing style according to the atmospheres of the soul, a participatory, musical and colorist style, whose essence is the freedom united to the fidelity."

Cintio, as a great connoisseur of Martí's work, warned that this fidelity is indissolubly linked to Martí's cosmovision of life itself, that is why he recalled the letter of July 1882 from the poet's mother, Doña Leonor Pérez, who with sharp wisdom critically sentences: "I don't understand about verses; for me it is in prose because it is written in reality."

These poems do not go to an autonomous realm, but they trace metaphors from reality”; they do not depart from it, they are closer to much later poets such as Gabriela Mistral or César Vallejo, closer to the poetry of today and tomorrow.

That is why everything presented in this poem book persists in our memory, even the words of the dedication: "Son: frightened of everything, I take refuge in you. I have faith in human improvement, in the future life, in the usefulness of virtue, and in you. If someone tells you that these pages are like other pages, tell them that I love you too much to desecrate you like that. As I portray you here, so have my eyes seen you. With those fancy clothes you have appeared to me. When I have stopped seeing you in one way, I have stopped portraying you. Those streams have passed through my heart; I hope they reach yours!"

How beautiful to tell us that her refuge is in the innocence of his son, not as an asylum as is understood in the art of Julián del Casal, but as a grip that embodies innocence, but also another force dynamically linked to the future world.

"Her creed has three dimensions: a social one (human improvement), a religious one (the future life) and a moral one (the usefulness of virtue). The three are linked by a dynamism of future that beats, as we saw, in the very idea of the son; not only antidote, by his innocence, against the poison of the world, but also, insofar as that innocence is germinal force of life, impeller of future". And this usefulness of virtue has its functionality because it works for the future.

There is a lot to be calibrated in these lighted verses and to place their spiritual context, because as Cuban poet Fina García Marruz, Queen Sofía Poetry Award and Pablo Neruda, emphasized about the transcendence of this poem book in our arts, "these verses, because of that painful background covered with lightness, are perhaps among the most Cuban he wrote. In that same language of Ismaelillo, of our hummingbird, firefly, and flying elf, which will later be made in the free verses speaking of whirlpool, sparks of fire, painful enjambment or sudden islands of light."

Deje un comentario