Cuban writer Teresa Cárdenas Angulo is, in addition to being a sensitive storyteller, television scriptwriter, actress, folk dancer and social worker. He has won several awards in the literary field, including the Casa de las Américas Prize and the Critics Prize obtained in 2005 for Perro viejo , novel for young people. She is also the author of Cuentos de Macucupé , published in 2001; Tatanene Cimarrón in 2006, and Cuentos de Olofi in 2007. Ikú and Barakikeño y el pavo real were two of his widely accepted titles, appearing in bolsibook format in 2007 and 2008 respectively, by theEditorial Gente Nueva .

In 2013 his epistolary novel Cartas al Cielo was included in the Twenty-one Collection, one of his most controversial and realistic creations. In it, Cárdenas Angulo narrates the childhood and adolescence of a black girl within the family characterized by poverty, racism and violence, despite being made up of women, except for sporadic male presence. The little girl writes letters to her deceased mother, having no option to communicate normally with the other members of the family, who have welcomed her reluctantly after being left helpless in the face of her father's cowardly flight and subsequent maternal death. For this cause he will suffer, and every detail of his grief will be revealed by whoever writes, always in the first person singular, a resource that could well refer to some autobiographical glimpse, or the astute and well-achieved intention of identifying ourselves psychologically with the vicissitudes experienced by the protagonist.

The author places the reader on the same thorny path as her character, in the same environment of darkness and enclosure, through a language marked by the presence of marginal vocabulary and negative meaning in repeated mentions of death, suffering, illness, the burials, the sadness, the physical abuse. It literally mentions teasing, hitting, pinching, shoveling, scraps with wedges, punching, scratching, fisting, hair halons, shoving, slapping, arguing, yelling, offenses, threats, which is overwhelming, especially for readers of the same age who do not face this reading as a way of family or social exorcism. Another terrible pattern is the suicide of the mother, the triggering event of the plot, which makes the girl blame: "You and Dad were happy until I was born and everything was spoiled."

The narration is enriched with detailed descriptions of Afro-Cuban rituals from two perspectives: positive, insofar as a belief that offers footholds to the harsh existence through faith; and negative, as they are taken as a motive for the injury to the girl. Other ethical dilemmas manifest themselves: the mother had joined her own sister's husband; therefore, there is a common father that will be discovered in due course; likewise, the aunt's children come from different parents. Male alcoholism appears linked to sexual abuse and family ineptitude; Vice personified in the figure of the stepfathers of the cousins, who will be defended by the girl. All this unleashes a multitude of interpersonal and intra-family conflicts from a perspective close to hyperrealism.

The little girl evokes her mother through dreams and visions, memories and smells offered as appealing resources in the diegesis, and projects escape routes to her situation. To do so, the country chosen is France, based on contact with a book lent to her by the teacher, Silvia, characterized as smiling and intelligent, who welcomes the girl into her own home and offers her protection and security never before experienced. for her. This manifests the need to escape from the minor, but to white Europe. A manifest impotence in the critical comparison with the opposite assumption is perceived in the character's design, fostered by the offenses she receives from her family: faced with the constant denomination of "bembona" that her own family applies to her, the girl says to herself herself that, if she had the colors and features of a white person, she would be "hideous." However, she is attracted to her friend Roberto, "the white boy in the classroom", which gives the measure of the involuntary and unconsciously assumed acceptance of her grandmother's criteria about the apparent superiority of whites and the convenience of their closeness. . To this is added her own definition as "the darkest in the classroom", since on no occasion does she explicitly recognize herself as black, she never mentions this word, neither in the singular nor in the plural of the feminine gender, despite consciously stating at other times their criteria and refusing to use the hot comb to straighten their hair, thus protecting their ethnic identity. These contradictions evolve and disappear, feeling sincerely inclined towards your friend, as it really happens when it grows and matures, generally through facing very negative experiences, from which it gets hurt but does not lose its kind essence and its regenerative capacity, the result of a firm intelligence that makes it shine and contrast among the rest of the characters. Finally, he agrees to the love of the young man, whose mother prostitutes herself with foreigners, the reason for such a great suffering for the boy as the orphanhood of his friend, an equivalence whose intensity brings them closer spiritually in a relationship that will serve as a shield against family and social prejudices. . fruit of a firm intelligence that makes it shine and contrast among the rest of the characters. Finally, he agrees to the love of the young man, whose mother prostitutes herself with foreigners, the reason for such a great suffering for the boy as the orphanhood of his friend, an equivalence whose intensity brings them closer spiritually in a relationship that will serve as a shield against family and social prejudices. . fruit of a firm intelligence that makes it shine and contrast among the rest of the characters. Finally, he agrees to the love of the young man, whose mother prostitutes herself with foreigners, the reason for such a great suffering for the boy as the orphanhood of his friend, an equivalence whose intensity brings them closer spiritually in a relationship that will serve as a shield against family and social prejudices. .

The problems of racism and poverty are centered on strong inherited traditions and well marked by a historical family past, which is exposed in the character of the grandmother, with an imposing and abusive personality, contrasted with her contemporary Menu, the kind and hospitable lady who sells flowers, who is even poorer and has also lost a son. The importance of the character of the grandmother is such that it is the word that is mentioned the most in the work after those referring to the mother, the main motif of the text —mamá, mamita-, followed by “aunt”, from which it can be inferred the relevance that the dismal adult trio acquires by marking - and subduing - the girl's long-suffering life with its follies. One of the major dramaturgical oppositions evident in the novel is this, at one of whose extremes is that retrograde entity, a sort ofBernarda albaCuban, whose parliaments are practically sentences, very negative in content and form. She is the ultra-conservative and conformist voice that dictates the most prejudiced ideas and prevents the rest of the family from advancing socially, made up of her two daughters and three granddaughters. In his mouth are the advice to "advance the race" through mate selection, the praise of whites compared to blacks, the supposed advantages of working for them in a frankly subordinate social position, and the violent mistreatment inflicted the granddaughter who rejects, among other causes, for being the darkest skin and having the most accentuated features. The character is connotatively recessive, but despite this, or perhaps because of it, the final forgiveness granted by the injured young woman to the almost dying old woman shines brighter,Teresa CardenasHe works it very wisely as the climax of his novel, contrasting past negative actions with the protagonist's present care towards the sick woman, as well as towards her offensive cousins, one of them turned sister by her father. In this way, forgiveness stands as a notion of supreme value that generates understanding and growth on a higher symbolic plane, and at the same time, the ability to advance towards the future, towards the self-construction of true ethical and moral values. Forgiveness will equally encompass the mother in her ill-advised decision to abandon her, for which the writer of the image of the kite and the birds is used as a metaphor alluding to the will to let the memory go free, producing a feeling of real relief on readers. This forgiveness also includes the father, when starting your search for the purpose of a rescue, an approach, a search of the ground; and not of a reproach or a complaint towards his punishable act.

Despite the very strong theme, considered taboo in a still recent past, the work is fortunately legitimized by awards and publications. Specifically, he received the David and the Hermanos Saíz Association Award for best text, both in 1997, and the National Prize for Literary Criticism in 2000. Its inclusion in the Twenty-One Collection of Gente Nueva is an endorsement of the treatment of topics allusive to unfulfilled social guidelines, visibility of families that suffer various types of affective and operational dysfunction, and psychological and sociological conflicts that pass - always and in the first place - by personal acceptance in different spheres, such as those of gender or sexual orientation and racial or ethnic, for which a timely education is necessary - absent or inverse in this case - for this to happen happily.

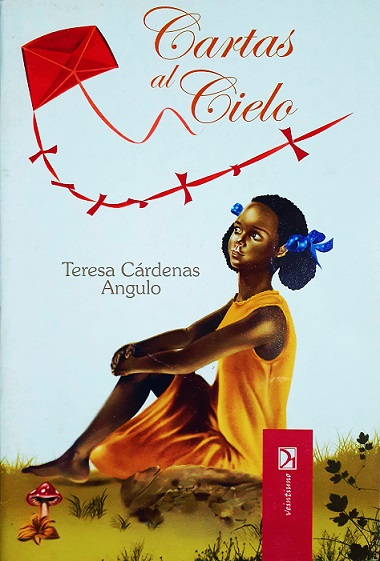

The design of the book respects the collection profile bequeathed by María Elena Cicard Quintana . The edition is by Suntyan Irigoyen Sánchez and the design and composition by Mariela Valdés López . The interior and cover illustrations belong to Yalier Pérez Marín, who offers a tender and friendly vision of the protagonist through an excellent hyper-realistic drawing of outlined lines and careful shadows and gradations that give the illusion of volume and spatial depth, which illustrate the minor's personal tragedy in highly accomplished expressions, and They also characterize the secondary characters whose attitudes will shape their strong spirit. The excellence achieved in this intimate relationship of form and content, with an external appearance consistent with the internal text, are an added foundation to make Letters to Heaven one of the most interesting, challenging and truthful options in current Cuban literature for children. youth and also for adulthood.

Deje un comentario